Domain

Domain is intended to be an intervention on the viewing space of painting. The artworks are an expansion from traditional rectilinear painting by becoming a total frame for one central painting which hangs above the mantelpiece. Domain engages with the interrelationships generated between notions of outside and inside, frame and painting, gallery and artwork. The work highlights an ‘architecture of display’ to collapse the material and conceptual thresholds of painting such as surface, and frame.

The objects in this series are both frame and painting; real and simulated; interior and exterior; product and package. This configuration inverts the picture plane into real space. Architectural elements engage with the gallery and the viewer, forming a relationship that is both familiar and out of place. The installation’s scale activates both a museological and domestic setting; where the reciprocity between the work, the gallery and the viewer becomes the threshold between art and life.

By engaging in a discourse on art, my practice has become increasingly aware of defining systems in art like medium, the frame, and the gallery; outside forces that take an imperative role in shaping how art is perceived, defined, and valued.

The objects in this series are both frame and painting; real and simulated; interior and exterior; product and package. This configuration inverts the picture plane into real space. Architectural elements engage with the gallery and the viewer, forming a relationship that is both familiar and out of place. The installation’s scale activates both a museological and domestic setting; where the reciprocity between the work, the gallery and the viewer becomes the threshold between art and life.

By engaging in a discourse on art, my practice has become increasingly aware of defining systems in art like medium, the frame, and the gallery; outside forces that take an imperative role in shaping how art is perceived, defined, and valued.

Joe Wilson.

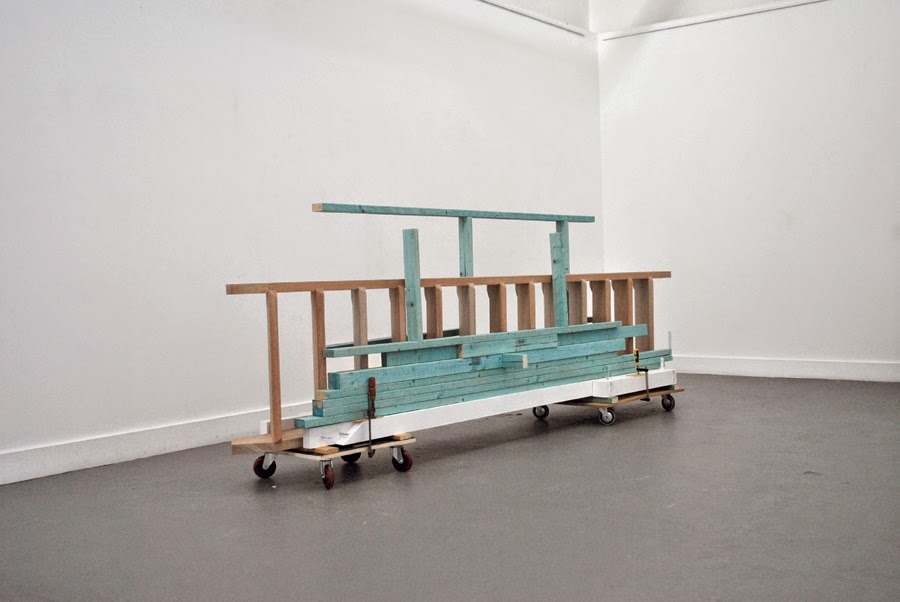

PROCESS IMAGES

The following is a copy of my investigation report for my honours year at the National Art School, 2014. Due to the format of this website, footnotes and images (figures) have not been included in this publication.

STUDIO INVESTIGATION REPORT:

Framing Painting

Joe Wilson. BFA (Hons) 2014

TOPIC

Framing Painting: An examination of how painting functions in space, in relation to historical perspectives on the object, viewer, and context of presentation.

Framing Painting

Joe Wilson. BFA (Hons) 2014

TOPIC

Framing Painting: An examination of how painting functions in space, in relation to historical perspectives on the object, viewer, and context of presentation.

DESCRIPTION OF ARTWORK

The nature of the work created is an installation entitled Domain (figure 1 & 2). The Domain installation features domestic architectural elements of a living room, positioned as an extended frame to a painting.

Elements of the Domain installation as they will be referred to hereafter:

The nature of the work created is an installation entitled Domain (figure 1 & 2). The Domain installation features domestic architectural elements of a living room, positioned as an extended frame to a painting.

Elements of the Domain installation as they will be referred to hereafter:

- Window (Partial View): a representation of a window framed in a stud wall

- Partial View (Threshold): A reductionist landscape painted on stretched polyester.

- Easel Painting (Green): A geometric shaped, monochrome painting, on board, displayed on a customised easel.

- Hearth: A timber mantelpiece.

- Flight of Stairs: a timber staircase.

FIELD AND CONTEXT

The area of enquiry most significant to the development of my work relates to what painting is and how it functions in space historically, and presently in my practice. Investigation of object, systems of value, and notions pertaining to the threshold; as expounded by key writers such as Michael Fried, Jean Baudrillard, and Brian O’Doherty, and artists including Frank Stella, Geoff Kleem, and Stephen Little, who have been particular focal points in the development of that enquiry.

OBJECT AND OBJECTHOOD: PAINTING, OBJECT AND SPACE

The Condition of Non-Art

Art critic Michael Fried in his 1967 essay Art and Objecthood investigates Minimalist art, which he calls Literalist art, and the claim this style has to the modernist tradition in terms of the look of non-art and literal object. Fried calls the condition of non-art, “objecthood”. He asserts that, “…modernist painting has come to find it imperative to defeat or suspend its own objecthood.” This relates to the painted canvas as an object, but not being seen as such. Fried points out that modernist artists searching to escape pictorial illusionism had come to emphasise the shape and support of the picture plane, using Frank Stella as an artist example. However, for artists Donald Judd and Robert Morris, whom Fried criticises, the solution was three-dimensional. Fried’s objection to this solution is not just based on the value identity of art as such, but has to do with the synthesising of the domains of painting, and sculpture.

My work fits within this field of discourse in that elements may be seen as literal. Flight of Stairs and Hearth are replicas of literal, or ‘real’, stairs and hearth, from my own living room, that, if installed in place of the original would function as such.

The Beholder

My work fits within this field of discourse in that elements may be seen as literal. Flight of Stairs and Hearth are replicas of literal, or ‘real’, stairs and hearth, from my own living room, that, if installed in place of the original would function as such.

The Beholder

Theatricality is a second non-art attribute Fried associates with Minimalism. Rather than being self-contained, the minimalist object is concerned with the situation in which it is seen, the object has “presence”, and therefore “the experience of literalist art is of an object in a situation – one that, virtually by definition, includes the beholder.” Subject is transferred from the object to the viewer. Fried’s objection to the presence of the work was a lingering attachment to Modernist conventions. Conversely, critics Douglas Crimp and Rosalind Krauss, argue in the positive; Fried’s theatricality, in requiring the presence of the viewer, can be seen as being used by minimal art to attack the “artist’s interiority” or “private myth”. The prestige of the artist is transferred to the prestige of the viewer “whose co-presence with the minimal object is necessary for its completion.”

The Domain installation is an environmental situation that acknowledges the viewer by altering the viewing space. The objects pertain to a domestic space which indicates somebody to be either present or absent.

Anthropomorphism: Viewer Self-awareness

The relational interaction between object and viewer pertains to anthropomorphism. A characteristic Fried associates with minimalist works, and a character that Morris and Judd reject, in regard to modernist relational composition. Anthropomorphism, when not interior to the work itself, relates to the perception of artworks, and the interiority of the viewers gaze.

In his thesis Painting in Transit, contemporary artist Stephen little, examines the minimalist object in association with “a blank ready-made canvas” and monochrome painting; in regard to the viewers gaze. Using monochrome painting as an example, Little emphasises that without pictorial illusion, “the viewer is now forced to look at instead of into” the object before them.

"…the viewer’s gaze is instead suspended in literal space. In this his or her looking becomes self-aware. By gazing at an object in real space the object reflects or mirrors one’s gaze." (Little)

Similarly, artist and writer, Brian O’Doherty examines the role of the “Eye and the Spectator” in his seminal essays “Inside the White Cube”(first published 1976). For O’Doherty, self-awareness, “looking at ourselves looking”, creates uncertainty in the perceptual process, and in turn erodes “any certainty about what’s out there.”

This line of investigation led me to contemporary artist, Geoff Kleem’s work. Kleem’s interdisciplinary practice involves photography, object, and installation. Kleem emphasises the photo as object by disrupting pictorial illusion with surface interruptions, physical location reference (e.g. GPS coordinates), and emphasised armature (figure 8). Writer Anthony Gardner argues,

"…the works make transparent their status as constructions: the exposed armature and blocked views reveal the works’ ‘architecture of display’, making the act of looking more active and self-reflexive." (Gardner)

In view of self-aware looking, or self-reflexivity, Easel Painting (Green) is a monochrome, with regard to Little’s looking “at” instead of “into”. It is also a painting where the relation to the support is emphasised through the use of a shaped surface, (in line with Stella) and the customised support/easel, acts as an “exposed armature” drawing attention to the object of the work to be looked at. Domain is, as a body of work, the armature to Partial View (Threshold); as a domestic setting, the accompanying works can be read quite literally as “the architecture of display” similarly to Kleem as afore mentioned.

In view of self-aware looking, or self-reflexivity, Easel Painting (Green) is a monochrome, with regard to Little’s looking “at” instead of “into”. It is also a painting where the relation to the support is emphasised through the use of a shaped surface, (in line with Stella) and the customised support/easel, acts as an “exposed armature” drawing attention to the object of the work to be looked at. Domain is, as a body of work, the armature to Partial View (Threshold); as a domestic setting, the accompanying works can be read quite literally as “the architecture of display” similarly to Kleem as afore mentioned.

Activating the Space

"As modernism gets older, context becomes content. In a peculiar reversal, the object introduced into the gallery ‘frames’ the gallery and its laws." (O'Doherty)

For O’Doherty, the gallery, like the viewer, has become present in the content of art. He observes in regard to Stella, that the “breaking of the rectangle formally confirmed the wall’s autonomy”. The gallery space becomes active, the wall is activated; Stella’s 1962 exhibition at Leo Castelli’s Gallery of striped U-, T-, and L- shaped paintings (figure 9) “developed, every bit of the wall, floor to ceiling, corner to corner.” O’Doherty explores how the gallery operates as a privileged space of art:

"Initially the picture plane is an idealised transforming space. The transformation of objects is contextual, a matter of relocation… When isolated, the context of objects is the gallery. Eventually the gallery itself becomes, like the picture plane, a transforming force. …as Minimalism demonstrated, art can be literalised and de-transformed; the gallery makes it art anyway." (O'Doherty)

My work aims to activate the space in which it is viewed by transforming the support mechanisms, and therefore the space in which they exist, in such a way that alludes to their inclusion in the work rather than a separation from it. Domain indicates how the transformation of objects is contextual when they are viewed in a gallery setting and how that setting may redefine how those objects function. When the picture plane is ‘realised’ the gallery becomes tableaux.

My work aims to activate the space in which it is viewed by transforming the support mechanisms, and therefore the space in which they exist, in such a way that alludes to their inclusion in the work rather than a separation from it. Domain indicates how the transformation of objects is contextual when they are viewed in a gallery setting and how that setting may redefine how those objects function. When the picture plane is ‘realised’ the gallery becomes tableaux.

AUTHENTICITY AND SPACE: SYSTEMS OF VALUE

The Gallery as Authority

O’Doherty observes the modern gallery as a kind of proto-museum, set apart from the world. Objects within occupy a timeless setting that confers the appearance of art already having entered into posterity. He argues that art is a:

"…product, filtered through galleries, offered to collectors and institutions, written about in magazines partially supported by the galleries, and drifting toward the academic apparatus that stabilises ‘history’ – certifying, much as banks do, the holdings of its major repository, the museum. History in art is, ultimately, worth money. Thus do we not get the art we deserve but the art we pay for." (O'Doherty)

These ideas have necessarily influenced my view of framing painting within the gallery system and how it is viewed in that realm, being particularly aware of value, in the sense of ‘product’. I have explored packaging in reference to the idea of how the gallery as a frame may serve as packaging in the marketplace. The installation as a frame may be seen as both displacing and pointing to this authority by providing its own system of viewing, therefore disrupting the gallery influence while unavoidably acknowledging its power to identify the work within the convention of art. As O’Doherty suggests,

"The classic modern gallery is the limbo between studio and living room, where the conventions of both meet on a carefully neutralised ground. There the artist’s respect for what he has invented is perfectly superimposed on the bourgeois desire for possession." (O'Doherty)

Baudriallard: Transaesthetics

This investigation of the signs and value systems includes French social theorist, Jean Baudrillard, and his theories on the role of images, transaethetics, and consumption. For Baudrillard, the role of art has undergone change through its increasing proliferation. Modernity, he argues, has liberated all spheres, including art. The belief in representation or anti-representation, criticism or anti-criticism has been liberated; he calls it an “orgy of the real”. Objects, signs, and ideologies alike have been overproduced, and the value that may have existed once no longer has any point of reference. They disappear in an “endless process of self-reproduction”, simulation, freed from their respective essences they continue to function, only now, indifferent to that essence. Kim Toffoletti says that:

"Baudrillard has commonly been aligned with proponents of post-modernism like Jean Francois Lyotard, and Frederick Jameson who chart the shift away from the certainty of modernist grand narratives and coherent categories through which to order and understand the world. In it’s place is substituted a pluralism of styles, a collapse of aesthetic values and hierarchies, and an interrogation of the distinction between ‘representation’ and ‘reality’." (Toffoletti)

In the book Baudrillard Reframed, author Kim Toffoletti bundles Baudrillard's oeuvre of writing into major themes such as “Art as Null”, “The Conspiracy of Art”, and “Consumption”. This clarification of Baurdiallrd is important to my research, where the work is chiefly concerned with the ideas of representation and reality, due to the re-creation of real objects and the systems of viewing that pertain to consumption and product, as previously argued. I see that all these systems provide framing mechanisms of consequence to my work in relation to contemporary philosophical views and hierarchies of value. Toffoletti further argues that:

"By existing in a referential dance with signs and symbols from everyday life, as well as with prior art movements, contemporary art nullifies itself by surrendering any power it might have had as aesthetically unique." (Baudrillard)

What Baudrillard calls “transaesthetics” is brought about by an ever-increasing proliferation of signs, a mix of all cultures and styles, where everything has been aestheticised, “manufactured into a sign for consumption.” Toffeletti outlines Baudrillard’s ‘conspiracy of art’: where institutions and the system of the art world mask the disappearance of art by upholding the idea of an exceptional art. Commodification too, maintains value in art, obscuring its nullification. Transaesthetics reasons that when everything is aetheticised, art is both everywhere and indistinguishable, and so, disappeared.

In relation to aesthetics and the disappearance of art, art critic and philosopher Arthur C. Danto plays down the role of aesthetics as an identifier of art, in his essay After the End of Art and his defending essay The End of Art: A Philosophical Defence. When art becomes indistinguishable in appearance from non-art, it is the concept or meaning in the work, what he calls “aboutness” that signifies it as art. Danto qualifies:

"An artwork, in this sense, embodies its meaning when it is seen interpretatively. …The ‘highest reality’ of art is its own essence, brought to self-awareness." (Danto)

Toffoletti does however argue, that for Baudrillard, art loses its function as a critical medium by becoming a sign with no special claim relative to other signs.

For the purposes of my studio led research, ‘self-awareness’, as Danto puts it, becomes a core strategy or goal, especially in regard to the aesthetic form of the work, and how the appearance corresponds to commodity and product. In regard to Baudrillard: at the heart of the ‘real’, is a question of authenticity; and so the question also arises, does my work simulate ‘product’? or does it simulate ‘art’?

"Creators and consumers’ simulate their roles, playing these parts in a way that surpasses mere imitation. They appropriate how artists and consumers act so closely and consistently that it becomes our reality of how art is made and looked at." (Baudrillard)

ARCHITECTURAL THRESHOLD & CONCEPTUAL THRESHOLD

Architecture of Display

An examination of the history of the frame parallels shifting priorities of painting. In her essay Frames, art writer Barbara Savedoff examines the importance and function of the frame. She identifies that the frame plays an important role in the “presentational context” of artworks. Savedoff locates the independent, detachable frame as developing, to accommodate and safeguard, the mobility of the easel painting. Early Modernist artists such as Degas, Kandinsky, and Whistler gave special importance to the frame; however, Savedoff observes that contemporary artists tend to place less emphasis on the frame, where the frame is either absent, or generic.

Savefoff elucidates the function of the frame. It can be decorative, protective, or act as a sign to show value. The frame can serve to insulate the painting from its environment. In twentieth century modernist painting, the abandonment of the frame contributed to the white wall imperative of the modern gallery. The frame mediates between room and painting, facilitating pictorial illusion. By hiding the edges of the canvas, objecthood is suspended. The frame can reference the window, which can allude to the viewer becoming voyeur, through which is seen a private space. The frame can enliven or echo the compositional elements in the painting. The frame as boundary or edge can “play between the real shape of painting and the shape within” as exemplified Stella’s shaped supports.

Savedoff's essay is perhaps the most relevant document relating to my project as an investigation of the literal picture frame, by bringing to awareness the place and role of the frame. In reference to painting becoming an extension of the frame, as is the case with Stella, it is possible to hypothetically reverse this idea, to see the frame as becoming an extension of the painting.

As an artist example, Kleem’s 2002 photographs, on timber easel-type mounts (S35˚ 09’ 53” – E150˚ 34’ 35” and S35˚ 09’ 35” – E159˚ 34’ 35”)(figure 10.), extend the support of the photo, making it consciously a photo-object. Making the experience of the 2D image incomplete without spatially experiencing the photo and its support, Kleem makes difficult, “spatial perception, with physical immediacy”, “by overtly staging the photograph as both object and image.”

Interior/Exterior 1

Duncan P.R. Patterson, architect and designer, in his paper, There is a Glass Between Us, examines the role of the window and other architectural thresholds. This research is relevant because of the key architectural elements in the Domain installation, all of which are literal thresholds. The threshold is neither inside or outside, upstairs or down. Patterson describes the dynamic forces in a living room as being centripetal to the hearth, and centrifugal to the window. Windows bring the outside in and the inside out, mediating between interior and exterior ecologies; the window sets a limit in order to define one relative to the other. Patterson argues that everywhere there is a window, there is a partial view framed,

"…revelations of who we are, available for popular consumption. These temporary revelations are examples of the very predetermined crossings of boundaries implied by the very existence of boundaries in the first place." (Patterson)

This speaks to the development of identity, by reciprocal exchange, interior and exterior ecologies are “produced simultaneously as they communicate back and forth, in part through the window.” Identity here refers to the domestic in relation to the public, and also the individual to society. Philosophically, this reciprocity can relate to identity domains that define painting, art, and even language.

Interior/Exterior 2

Little’s thesis aforementioned, references Krauss, who examines identity domain in regard to the theory of grammatology and the theory of the parergon by Post-Structuralist Jacques Derrida. Here, the consensus is that “the idea of an interior set apart from, or uncontaminated by an exterior” is a “metaphysical fiction”. For example the ‘interior’, art, cannot be understood without the ‘exterior’, context, of the gallery. This deconstructive argument sets about challenging prescriptive categorisations, like Fried’s desire for object “to defeat or suspend its own objecthood” in order to identify as art, and not theatre (non-art). The deconstructive argument is for objects and actions to not behave, in a correct sense, interior to the convention to which they relate.

Concerning interiority and exteriority, the frame around a painting may be seen as a mediator between worlds, between what is conventionally thought to be the painting, and what is not. Acting as a boundary that is neither in one world or the other, where, alternatively, the frame is an extension of the painting, and therefore, the installation, Domain, may be an extension of the frame, and thereby, perhaps the painting itself. This provides an interesting “place of exchange between painting and what painting is not, and in this sense is a shifting space of ill-charted flux” that allows for further exploration of the changing essence of the material and ideological identity of painting.

Little’s thesis, Painting in Transit, explores and puts forward, ideas related to “unfamiliar painting”, where the physical elements and actions may be removed, but painting is still inherently present and the name painting applicable. Little supports his position on painting by a “well-documented point of closure in the recent past that sign posted that a blank ready-made canvas could be a painting” and also through nomination, whereby choosing takes precedence over making. In his studio led research, Little pursued a discourse of painting “from the outside rather than from within its standard terms of reference.” The resulting work functioned either as about painting, or as painting. Monodome (Pink) (2010)(figure 11), a tent on the wall, references monochrome painting and geometric abstraction. Vacuum Painting (2007) (figure 12), plays on a reversal of painterly conventions.

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Central to my research on framing painting has been an examination of the identity or domains that distinguish painting, and art. How the domain or the conceptual space crosses over into the physical framework. The gallery plays a role of legitimatising, and conferring art to objects. Self-awareness too, is a repeating qualifier for art, in the case of the making, on behalf of the artist, and looking at looking, on behalf of the viewer. All of which influence the role of the frame.

In regard to painting, as a categorical domain, it is possible to self-identify with that domain without the proper appearance of painting, so long as signifiers, or even the negation of signifiers, are aligned to a historical and theoretical discourse on painting. Antithetical gestures don’t seem to seek to abolish what they oppose, but rather open new lines of potentiality. Thereby opening up the interpretation of the frame in regard to painting to include not only the physical supports and surroundings of painting but also the viewer and the cultural realities in which it exists. This blurs the lines between categories; creating painting without easily definable edges. Where the ‘what is’ and the ‘what isn’t’ are never entirely distinguishable as one or the other.

The installation Domain is both the frame and the painting; the real and the simulation; of interior and exterior, the product and the packaging, art and the everyday, that aims to support an investigation of how painting functions in space by referring to each domain in which painting may be framed but being defined entirely by none.

STUDIO PRACTICE

STUDIO PRACTICE

The process that led me to conceive of my honours project involved observing aspects of my Studio (2013) installation (figure 13). What interested me specifically was the back wall of the room (figure 14), which formed a kind of combine (in the spirit of Rauschenberg’s combines), consisting of gyprock, ply, a blank canvas, and paint tins beneath a single level shelf. My observation was: that this wall could be considered a completed artwork, a painting. For me, the Studio, as a whole installation, confused the showing space of the gallery. The main question that was raised for me was, what was the situation of painting in this space? and where did the painting end and the support or frame begin?

I was inclined to pursue another environmental situation, and resolved to emulate my living room for my Honours project. My intention was to consider this space to be an alteration of the gallery, as a viewing space; and to consider the installation of everyday objects, as framing the picture (the painting). In the beginning, I considered the frame as a non-art element. I wanted to see the effect of over-substantiating the frame in relation to the painting that accompanied the installation. However, as my research progressed, I realised that it would be hard to display the everyday objects, the frame, as non-art, in the gallery setting, “…as Minimalism demonstrated, art can be literalised and de-transformed; the gallery makes it art anyway.” As referential cues to painting the objects in my installation could potentially claim to be painting, if understood in terms of an “expanded field”. But, the intention of the work is not to ask ‘what is painting’? so much as, ‘how does painting function in space’?

The first studio experiments were small constructed images, of landscapes, and then interiors. These three-layered constructed images mix up flat surface, perspective and literal depth. The two interior motifs entitled Inside the White Cube 1 and 2 (figure 16), were for me the most successful, for leading me to consider ideas of interiority and exteriority, as a physical presence and as metaphor.

As objects, the constructed images have a sharp visual aesthetic that I think takes on the look of a design product. In this way they have the look of a commodity. In a curious twist of logic, this led me to think that, in relation to Baudrillard’s transaesthetics and Danto’s view of the diminished value of appearance, the constructed images relate visually, more evidently to the everyday as an aestheticised product.

I have employed a reductionist approach to my subject, simplifying composition into limited colour blocks (figure 17). I paint in a manner that removes the artist hand by eliminating gesture. It has been my aim not to privilege the personality or skill of the artist, aligning the action of painting, through this technique, with the everyday labour of house painting.

The specific landscapes are fabricated, and without reference to actual location, they are generic (non-specific), stand-ins (signs) for landscape painting. It is important, here to distinguish the difference between referencing ‘all painting’, which pertains to a universality and history of painting, and, ‘a’ painting, which is relevant to a local narrative of painting domestically, in Sydney. I nominate landscape painting as a sign, a representative example of painting in the market place. In doing so, I identify my paintings with product. Because the work is intended to function on two levels, where on the one hand it functions as a well made aesthetic object, pertaining to the everyday (product), and on the other, functions at the “highest reality”, conscious of its own essence.

In a similar process of thinking, I packaged a painting and one of the constructed images (figure 18). These packages resonated with me, as the actual paintings can’t be accessed, they no longer function normally (i.e. on the wall) and can’t be seen except via the reproductions on the boxes. I found interesting associations in Geoff Kleem’s work. The packages place the paintings into a mode of transit, in-between destinations. Kleem’s wheeled sculptures (for example, Untitled 1993), as stated by art writer Wayne Turncliffe, “cannot fulfil a purpose beyond being displayed in the gallery or placed in storage.” The packages, will be part of an ensemble titled, Merch-tent, and will be on display in my studio space as part of the Post Grad exhibition. Merch-tent is a collection of several studies and objects that, together, form a small installation.

In the original design for my installation, Domain, I included large landscape paintings outside the room. I had wished to relate painting in a home with painting that existed outside in the world. I set about to produce six square format landscape paintings that would read as a single image. Upon completion I utilised the Building 25 Project space at NAS (figures 19-21) to frame and view the work. It was at this time that I was made aware that space restrictions for the Post-Grad show would eliminate the possibility of showing these paintings in conjunction with my installation.

Leading up to the installation in building 25, I worked on other components to contribute to the space. In the theme of environmental situation, I experimented with a bedroom motif. Using a stretcher bed, and side table. In reading Stephen Little’s doctorate thesis I could see an association that the stretcher bed had, as a modified blank canvas. I decided however that what I called Bed Ensemble (figure 22), wouldn’t contribute to my final project, as part of the Domain installation.

In preparation for the final project, I tested the effect of installing a painting above a ready-made mantelpiece in Building 25 (figure 23). It was an important step in deciding how to proceed. I knew that the mantel and staircase were a necessary component to my installation, but did I need to make them, or could I find and nominate them? The decision was influenced by the determining factor that I wanted to use a reductionist approach, and thereby have all the objects made from uniform timber. This would unify the work formally. The exception to this is the stud wall, built to frame the window; here, the difference (of timber) provides an exposed armature. The stud wall acts to frame the installation as a whole, in this instance.

In the original design for my installation, Domain, I included large landscape paintings outside the room. I had wished to relate painting in a home with painting that existed outside in the world. I set about to produce six square format landscape paintings that would read as a single image. Upon completion I utilised the Building 25 Project space at NAS (figures 19-21) to frame and view the work. It was at this time that I was made aware that space restrictions for the Post-Grad show would eliminate the possibility of showing these paintings in conjunction with my installation.

Leading up to the installation in building 25, I worked on other components to contribute to the space. In the theme of environmental situation, I experimented with a bedroom motif. Using a stretcher bed, and side table. In reading Stephen Little’s doctorate thesis I could see an association that the stretcher bed had, as a modified blank canvas. I decided however that what I called Bed Ensemble (figure 22), wouldn’t contribute to my final project, as part of the Domain installation.

In preparation for the final project, I tested the effect of installing a painting above a ready-made mantelpiece in Building 25 (figure 23). It was an important step in deciding how to proceed. I knew that the mantel and staircase were a necessary component to my installation, but did I need to make them, or could I find and nominate them? The decision was influenced by the determining factor that I wanted to use a reductionist approach, and thereby have all the objects made from uniform timber. This would unify the work formally. The exception to this is the stud wall, built to frame the window; here, the difference (of timber) provides an exposed armature. The stud wall acts to frame the installation as a whole, in this instance.

I have used timber as an industrial ready-made material, and have used processes that are characteristically diagrammatical, in reference to everyday labour, in order to diminish the objects claim to art, as artist-made.

In the final stages of my project I also tested Domain’s configuration, not into a room, but flat against the wall (figure 24). Configured into a room the composition is closed. This ‘closes down’ the interpretive seeing of the work. The objects become normalised by assuming functional positions, i.e. indicating a living room. The room configuration obfuscates the reading as art, in favour of the everyday. This fits more consistently with the aims of my investigation.

In the final stages of my project I also tested Domain’s configuration, not into a room, but flat against the wall (figure 24). Configured into a room the composition is closed. This ‘closes down’ the interpretive seeing of the work. The objects become normalised by assuming functional positions, i.e. indicating a living room. The room configuration obfuscates the reading as art, in favour of the everyday. This fits more consistently with the aims of my investigation.

DOMAIN

The Domain installation is a meditation on the space of painting. Hearth, Flight of Stairs, and Window (Partial View), form an extension of the painting, and frame the painting Partial View (Threshold). Easel Painting (Green), sits on the mantel as a reminder of painting as object. Domain is a meditation on the interrelation of the outside on the inside, the frame and the painting, the gallery and the artwork.

The interiority of the picture plane becomes reversed, into real space. The simulated environment blends reality and fiction, that of the original, and the represented. Objects can be read as literal and/or metaphor.

CONCLUSION: INSIGHTS AND OUTCOMES

This investigation set out to examine how painting functions in space, in relationship to historical perspectives on the object, viewer, and context of presentation. The key insights that have been considered are, object in relation to ‘objecthood’ and ‘theatre’, ‘anthropomorphism’ in relation to the viewer and the ‘architecture of display’; also, ‘self-awareness’ in art, and the threshold of difference in relation to interior and exterior domains, both physical and theoretical. These insights have, for my studio led research, informed the reading of literal objects in my installation, in regard to the everyday object, and the act of looking. Also, in revealing the role of the frame, and support, as a content-rich subject for further exploration.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ackermann, Marion. Fresh Widow: The Window in Art since Matisse and Duchamp Dusseldorf, Germany, K20 Grabbeplatz. 2012. An exhibition catalogue essay.

- Artschwager, Richard. “Table with Pink Tablecloth” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies (Vol.25, No.1, 1999) http://www.jstor.org/stable/4112982 (accessed August 11, 2014).

- Baudrillard, Jean. Simulations. New York, NY.: Semiotexte, 1983.

- Baudrillard, Jean. The Transparency of Evil: Essays on Extreme Phenomena. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Verso, 2009.

- Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author”, UBUWEB PAPERS (1967) http://www.ubu.com/aspen/aspen5and6/threeEssays.html#barthes (accessed September 9, 2014)

- Crimp, Douglas. On the Museum’s Ruins. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1993.

- Crimp, Douglas. “Richard Serra: Sculpture Exceeded.” October (Autumn, 1981) http://www/jstor.org/stable/778411 (accessed February 22, 2014)

- Danto, Arthur, C. After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Danto, Arthur, C. “The End of Art: A Philosophical Defense” History and Theory, Vol. 37, No.4 (December 1998) http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505400 (accessed September 17, 2014).

- Eco, Umberto. Travels in Hyperreality. London, SW10 9PG.: Picador, 1987.

- Foster, Hal, with Gordon Hughes, ed. Richard Serra. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000

- French, Blair. “Geoff Kleem: Architectures of display” Eyeline 50 (summer 2002/2003) 93-97.

- Fried, Michael. Art and Objecthood: Essay and Reviews. Chicago, IL.: University of Chicago Press, 1998

- Gardner, Anthony. “Geoff Kleem: The Dream World of Images”, Art and Australia, 45/1 (Spring 2006), 90-97. http://geoffkleem.com/texts/geoffkleem_art_and_australia.pdf, (accessed June 23, 2014)

- Kellein, Thomas. Donald Judd: Early Work, 1955-1968, New York.: D.A.P., 2002

- Kohn, Adrian. “Judd on Phenomena.” The Rutgers Art Review: The Journal of Graduate Research in Art History Vol 23. (2007) 78-99.

- Kosuth, Joseph. Art after Philosophy and After: Collected Writings, 1966-1990. Cambridge, Mass,: MIT Press, 1991.

- Kotz, Mary, Lynn. Rauschenberg, New York, NY.: ABRAMS, 2004

- Leddy, Thomas. “The End of Art by Donald Kuspit.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (Winter, 2005) http://www.jstor.org/stable/1559147 (accessed September 7, 2014).

- Little, Stephen. “A Close Shave with Painting” Artspace (Column 2013): 1-9.

- Little, Stephen. “Painting in Transit: Inter-domain transfer and material reformation”. PhD. diss, Goldsmith Collage, University of London, 2010.

- Livingston, Marco. Kienholz: The Hoerengracht. New York, N.Y.: Pace Wildenstein, 2002.

- Lyotard, Jean Francois. The Postmodern Condition. Minneapolis, MN.: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

- McArthur, John. “The Look of the Object.” Assemblage (April, 2000) http://www.jstor.org/stable/3171308 (accessed September 17, 2014)

- O’Doherty, Brian. Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. San Francisco, CA.: The Lapis Press, 1986.

- Paterson, Tanya. Render. Sydney, NSW.: William Wright Gallery, 2011. An exhibition catalogue.

- Patterson, Duncan, P.R. “There’s Glass Between Us: A critical examination of ‘the window’ in art and architecture from Ancient Greece to the present day.” FORUM Ejournal 10 (June 2011) http://www.research.ncl.ac.uk/forum. (Accessed June 2014)

- Rubin, William S. Frank Stella. New York, N.Y.: The Museum of Modern Art, 1970.

- Savedoff, Barbara, E. “Frames”, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Vol.57. no.3 (Summer 1999) http://www.jstor.org/stable/432199 (accessed July 31, 2014)

- Seel, Martin. “Art as Appearance: Two Comments on Arthur C Danto’s After the End of Art”, History and Theory. Vol. 37, No. 4. (December, 1998) http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505398 (accessed September 17, 2014)

- Sontag, Susan. Against Interpretation. London, SW1V 2SA.: Vintage, 1996.

- Toffoletti, Kim. Baudrillard Reframed. New York, N.Y.: I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd. 2011.

- Tunnicliffe, Wayne. “Geoff Kleem” Contemporary – Art Gallery of New South Wales (2006)

- Unsal, Merve. “Minimalist Art vs. Modern Sensibility: A Close Reading of Michael Fried’s “Art and Objecthood”” ART AND EDUCATION (2010) http://www.artandeducation.net/paper/minimalist-art-vs-modernist-sensibility-a-close-reading-of-michael-frieds-art-and-objecthood/ (accessed September 9, 2014).

- Ward, Frazer. “Discomforts of Home” Artspace Sydney (March 2008): 81-85

- Ward, Frazer. “Geoff Kleem: Useless Things” Art + Text 52 (1995): 62-66

In The Making